Basic Information

| Field | Information |

|---|---|

| Name | Betty Hemings (Elizabeth “Betty” Hemings) |

| Born | c. 1735 |

| Died | 1807 |

| Status | Enslaved for most of her life; matriarch of the Hemings household |

| Primary locations | The Wayles household (Virginia); later Monticello, Albemarle County, VA |

| Number of known children | At least 12 children (multiple sources of family memory and records) |

| Notable children | James Hemings (1765–1801), Sally Hemings (c.1773–1835), John Hemings (1776–1833), Robert Hemings (1762–1819) |

| Occupations / roles | Domestic service, household management, market gardening from a Monticello cabin later in life |

| Net worth (legal) | None — enslaved people had no legally recognized personal net worth in 18th-century Virginia |

When I tell the story of Betty Hemings I don’t stand outside of it like a neutral camera — I step into the kitchen doorway, I imagine the creak of the stairs, the hush of a room where small hands learned trades that would carry them forward. Betty’s life is the kind of cinematic ensemble piece where the lead is steady, quiet, and absolutely central: she is the organizing force behind a family whose members become cooks, carpenters, seamstresses, butlers — skilled trades that shaped the households and histories around them.

Roots, dates, and the shape of a household

Betty was born around 1735, and she lived until 1807, a lifespan of roughly 72 years in which she weathered the shifting fortunes of the Wayles and Jefferson households. By the time John Wayles’ estate was divided (mid-1760s), Betty and many of her children moved into the orbit that would be called Monticello. Over the next decades—through the 1760s, 1770s, 1780s—her children were apprenticed and trained into roles that made the Hemings family indispensable to the Jefferson household and to the wider Richmond–Charlottesville world.

Her children — a practical table of names, years, jobs

Below is a compact ledger of the family members most often named in household records and family memory:

| Child | Approx. birth year | Role / note |

|---|---|---|

| Mary Hemings | 1753 | Seamstress; later lived with Thomas Bell in a long-term relationship |

| Martin Hemings | 1755 | Butler at Monticello |

| Betty (Betty Brown) | 1759 | Personal attendant in the Wayles/Jefferson household |

| Nancy (Nance) Hemings | 1761 | Weaver, skilled textile worker |

| Robert Hemings | 1762 | Bought his freedom (1794) |

| James Hemings | 1765 | Trained in France as a chef; manumitted 1796 |

| Thenia (Thena) Hemings | 1767 | Sold at various points; family memory preserved her name |

| Critta (Critty) Hemings Bowles | 1769 | Married a free man of color (Zachariah Bowles) |

| Peter Hemings | 1770 | Cook and kitchen worker after James |

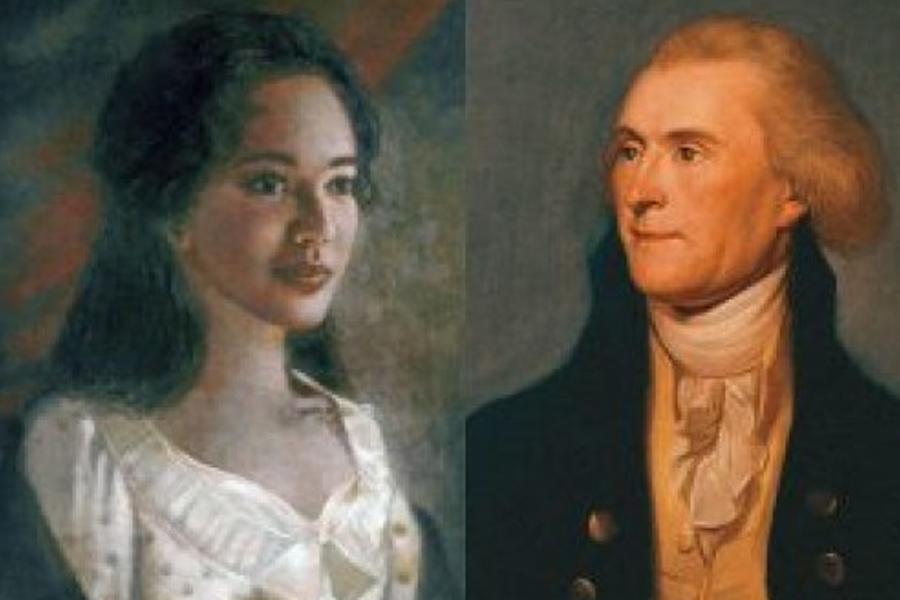

| Sally (Sarah) Hemings | c.1773 | Accompanied the Jeffersons to France; bore several children later associated with Thomas Jefferson |

| John Hemings | 1776 | Carpenter; freed in Jefferson’s will |

| Lucy Hemings | 1777 | Died young |

Those names read like a roll call of labor and craft — cooks with French training, a master carpenter, a butler who ran formal service, seamstresses who stitched clothes that moved in public and private life. The Hemings family skills were, in the language of their time, economic and indispensable; in the language of our time, they are testimony to talent and resilience.

Career, agency, and the limits of “work”

“Career” is a brittle word here — Betty and her children performed work that sustained people and homes, but they did so within a system that treated human beings as property. Still, inside that system Betty carved out roles that mattered: she managed households, raised children who became skilled artisans, and later in life ran a small, semi-autonomous economic life from a cabin at Monticello — selling cabbages, strawberries, and eggs to the estate and thereby creating a modest livelihood within profoundly limiting circumstances. Those details—dates like 1794 for Robert’s purchase of freedom, 1796 for James’s manumission—turn abstract history into concrete steps in a family’s arc.

Money, ownership, and the truth about “net worth”

If you are looking for a dollar figure for Betty Hemings — there is none to assign by modern accounting. Enslaved people were not legal owners of property; they were property. The economic reality of the 18th-century Chesapeake treated Betty’s labor and the labor of her children as assets on a ledger. Still, if “net worth” includes cultural capital, training, and a human network that produced chefs, carpenters, and storytellers, Betty’s wealth is enormous in the ways that matter to family memory.

The long echo — descendants, stories, and cultural afterlife

By the 19th and 20th centuries, Hemings descendants were telling their stories in memoirs and public speech — voices that kept family memory alive. In more recent times (the 20th and 21st centuries) the Hemings family figures have become part of national conversation: from museum work to archaeological digs around cabin sites, from biography to popular culture moments that reference Monticello. The Hemings name now anchors debates about family, power, and American history — and Betty sits, as she always did, at the center.

A personal aside — why I keep returning to Betty

I return to Betty Hemings because her life is pivot and seam. She is the hinge between two households, the mother who spun trade skills into survival, the quiet director behind a cast of talented—often brilliant—children. If history were a film, she would be the uncredited production designer whose touch makes every scene feel real.

FAQ

Who was Betty Hemings?

Betty Hemings was an enslaved woman born around 1735, matriarch of the Hemings family, and a central figure in the Wayles–Jefferson household at Monticello until her death in 1807.

How many children did Betty Hemings have?

Historical records and family memory identify at least 12 children, several of whom became notable tradespeople and household servants.

Was Betty Hemings related to Thomas Jefferson?

Betty was not Jefferson’s blood relative, but several of her children—by family tradition and historical documentation—were fathered by John Wayles, making them half-siblings of Martha Wayles Jefferson and deeply entwined with the Jefferson family.

Did any of Betty’s children gain freedom?

Yes — for example, James Hemings was manumitted in 1796, and Robert Hemings purchased his freedom in 1794; others were freed or had changed legal status at various times.

Did Betty Hemings have personal property or net worth?

Legally no — as an enslaved person she had no recognized net worth, though she later operated a small market activity from a cabin at Monticello that generated modest income.

Are there living descendants of the Hemings family today?

Yes — Hemings descendants continue into the present, and family memory, memoirs, and genealogical work have preserved many lines of descent and stories across the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries.